One night in Paris in 2011, Cary and I had a drink at the bar of the 5 star Hotel Regina. The atmosphere was strange. We were alone in this incredible 1900 decor, the waiters looked like they were from a Hitchcock movie and we saw a little mouse running around. This night inspired by the decadent atmosphere, Cary told me about one of his favorite book written by Joris-Karl Huysmans A rebours.

Now I understand his attraction for the eccentric anti-hero Jean des Esseintes, a symbol of the decadent spirit of the XIX century.

If you take a look at the artistic works of Cary, you find a tendency to dwell at the heights of artifice with an excessive taste for the strange, the unequalled of all kinds.

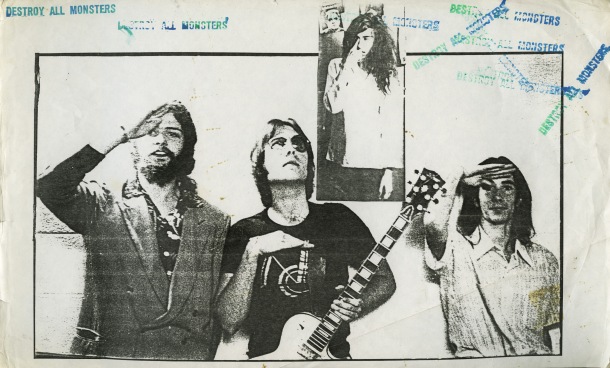

As the editor of Destroy All Monsters Magazine, and founding member of Destroy All Monsters (DAM) collective, Cary Loren injected his idea of art in total symbiosis with the members of the 70’s collective freshly out of adolescence: Niagara, Jim Shaw and Mike Kelley. The DAM zine is family album, a subliminal “mise en scène” to mythologize the band, a permanent mobile exhibition, a therapeutic treatment, a psychedelic camp trip into the underworld of the underground.

Encounter the multifaceted « ovni » Cary Loren, as a talk in collage, taking us into the mechanics of the DAM zine and other Detroit experiences.

Laura: Cary, influenced by all the monsters movies you saw, you start to make fan movies when you were 12 years old. Since this time and your apprentice with Jack Smith in 1973, your film practice became really intense. I really see a connection between your movie practice and the zine DAM. We find this attraction for the colour, the crazy montage, superimposition, etc., Did you make the zine in the same way you were making film?

Cary: Its a good question because connections between photography, art, writing (and all of life) can overlap in zines – and function in ways related to film or novels. The zine often works like a private diary or journal moving through time and taking on multiple subjects, narratives or points-of-view. I like how zines can overlap public and private worlds at the same time.

This wasn’t a conscious decision, but I’m reminded of how attracted I was to underground comics and tabloids of the ’60s: anthologies like Zap, Mad, Cracked and Weirdo. These were some of the godfathers of the zine movement.

The aesthetics of the ‘60s underground papers were fascinating; The Chicago Seed, The Berkley Barb, Sundance, The Sun, The Ann Arbor Argus, The Fifth Estate and the San Francisco Oracle: leftist tabloids with intense color, psychedelic design, and an anarchistic viewpoint. I wanted to achieve a similar aesthetic in DAM –a flashback in time.

A zine could become self-reflective, a source of poetry with its own secret codes and language: the zine as a contained poem.

The zine could breakaway from film or writing, allowing you to step aside and see the work in a different more playful chaotic (or static) way. It could be the outline you’re looking for, or the reason you no longer need to make a film.

Jack Smith’s theater was another influence – his films, writings, color slides, his Beautiful Book, his presence and apocalyptic imagery was fascinating. DAM was a homage to Smith’s exotica and a collage of visual obsessions. The world of silent films, the gestures of Marlene Dietrich, Andrea “Whips” Feldman, Jennifer Jones, Dorothy in Oz and monster films could all exist as neighbors in a book; images of extremity bouncing off each other. Smith validated what I was searching for and I blame Smith for the invention of DAM.

Finding solutions to making films and zines forced decisions such as buying outdated film, using scotch-tape splices, or printing on top of old flyers to save money on paper—a similar strategy in Smith’s trash-camp aesthetic.

An editor or artist/author has almost total control with the zine. They are the content supplier, manufacturer and distributor. The zine can be a song, a nocturne, a small enchantment, a multi-dimensional object, bending the boundaries and defying the form itself. The zine is propaganda art: to self-advertise, to convert, to rant, casting a spell, and can be a link to other projects in film, music or writing. Zine definition: The skeleton of a myth.

Laura: The idea you are talking about « zines can overlap public and private worlds at the same time” is really interesting. And if the zine can be highly personal it’s also a direct and clandestine interaction in the private sphere of the everyday life of the viewer. So what was the reaction of the viewer at this time in front of this zine transforming everything in a camp aesthetic? We can imagine that as an anti-rock band, the DAM zine was an anti-zine for this time ? Something like an ovnie in the landscape of zine, at this period, the majority of its pages were in black and white and were they related to one discipline (music, politique, comix, …) and seriously political ?

Cary: At the time of making the zine the audience was non-existent. On a simple level it was important to project DAM art to the public: to just get it out there. I don’t understand why the need came about, or why a thousand copies were printed of the first issue. Only a few record shops and bookstores were willing to distribute zines, and it took several years to sell out the first issue. Most were given away. I never heard from people who bought the DAM zine. There was never any feedback.

Making the zine was a way to keep the DAM collective together even as it was breaking apart. In ‘77 and ‘78 Kelley and Shaw were at CAL Arts in Los Angeles, I was thrown out of the band, moved to Detroit and enrolled at Wayne State University. Those were transitional years, and the zine documents that like a diary. By late ’78, Niagara was the only original member left in the band and Ron Asheton continued the music in a punk/rock direction.

It was an anti-zine for an anti-band. Our music didn’t circulate well until 1995, and still it remained a minor cult interest. There’s a schizophrenic nature to DAM. It had both a punk rock and a noise following. People mainly know the zine through the reprint Primary Information published in 2009, and the experimental music from the 3-CD set released on Ecstatic Peace! in 1994. Mass appeal will never exist for the kind of music we produced. It’s too abrasive and weird, resistant to popularity.

The zine framed and distributed our artwork and was a way to experiment with narrative and themes. Multiple disciplines were presented in each issue. For instance: issue #4 had a complete band history but it also referenced family rituals, the family photo album, holidays, underground films and the practice of photography.

The last two zines; #5 and #6 were centered around theater and film—an area I wanted to pursue further. They were assembled in Hollywood, California in ’78 and ‘79, and parodied film noir, horror, exploitation and romance through film stills. This collided with poetry, band lyrics, a reprint of Antonin Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty essay and fantasy /sci-fi illustrations. Kelley and Shaw works were also in the last issue, along with a promotion for Xanadu, made up of X-members of DAM: Ben and Laurence Miller, Rob King and myself. We were all dissatisfied with the punk (Asheton led) direction of DAM, so I began a small label and released two EPs on Black Hole Records: Days of Diamonds (1978, DAM) and Blackout in the City (1979, Xanadu).

DAM magazine was a blending of daily life and art, quoted alongside public artworks and figures in pop culture. The mixing of these spheres was a way to shape our identity, with both the public and private absorbing each other, transforming experience.

Zines are an open field where anything can enter. They can take on risky subjects: hallucinations, pop-stardom and serial killers, or can condense into a single subject: 8-track Mind, Hirsute Heroines and Dishwasher.

There was never a conscious decision to project a political ideology in DAM Magazine. We respected radicalism and hoped that came through in the artwork. We were bored with the Marxist-Maoist rhetoric and were somewhat miffed at seeing the hard left vanish in the night.

I wasn’t aware of many other zines in the ‘70s and there were few models to see at that time except in the world of sci-fi or fantasy-fandom. Music zines and art zines started to appear more frequently in the late ‘70s and were pop-culture oriented, mostly centered on punk— almost a return to the Beat era mimeograph revolution of DIY poetry and art zines.

Laura: The quality of the DAM zine and how you describe it sounds like it took quite a long time to make it. Is it for that reason you only made 6 issues in 3 years (1976-1979) ? or was it because as an anti-band rock you wanted to make a fewer releases of music, even if you made more zines than DAM records in this period ?

Cary: It took about a year to print the first issue, made mostly by high-speed offset lithography. I took classes at a vocational school and learned to use a copy camera, make halftones and operate the printing presses. I wasn’t the best printer and was embarrassed by how sloppy it all turned out. The issues never had the quality I wanted to produce or could afford. Most of the front covers were printed at a commercial print shop so at least they’d look well done.

I advertised our fist music release: Destroy All Monsters Greatest Hits cassette inside the first DAM issue and in the first issue of Lightworks Magazine. We sold less than thirty copies of the tape for $2 each. As the band evolved, its history and music were covered like news items in the zine.

In the summer of ‘78, I put together issue #5 in Hollywood and returned in ‘79, to layout issue #6. I almost stayed in Los Angeles but returned to attend Wayne State University in Detroit, where the last two issues were printed in the student print shop, volunteering there in exchange for printing the zine. Special copies of issue #5 contained a full color Xerox insert, an expensive process at the time. It was a slow complicated process, waiting until there was enough material to finish an issue.

It all came down to economics. Pressing records was (and still is) an expensive process. We wanted to do that, and were headed in that direction, but it was beyond us. Printing the zine was more realistic and there was an advantage to learning the process and working in print shops after hours.

Mike Kelley

Laura: Cary, in light of what you told me, I would venture an idea because its important for us to understand why the DAM zine has become cult apart from the fact of the originality of the DAM zine and the success of Mike and Jim who became two stars of the contemporary art scene. If the DAM zine was a way to continue the collective experience with the original group breaking apart : Mike Kelley, Jim Shaw, Niagara, can we say that the DAM zine is a kind of « mise en scéne » of DAM collective ? Maybe it’s more accurate to talk about your role as director of the scene rather than editor ? Unconsciously, you were using the fiction tool (cinema, theater, …) and the glamour of the color to construct a kind of story telling or fan-fiction ?

Cary: Yes, « mise en scéne » is a good description—and fan-fiction too. I wanted to include all our influences, to make a statement with images: something raw, exploitative, maybe shocking. Everything was thrown into the blender. The film and theater influence helped create a setting for the zine too.

Kelley later described DAM as a work of sculpture or method for his art: “This band was my painting strategy made flesh,” he said. Perhaps that idea arose from the practice room being adjacent to his bedroom. It was a very messy space next to his immaculate living area. At the time of DAM, Kelley’s work was rough, fiery, grotesque and cartoonish. It was passionate without a conceptual edge. The practice room may’ve been an intrusion or invasion of privacy, but it also enabled some subversive rawness.

Shaw’s paintings had a surreal collaged element and an abstract way of using the figure that came closest to the aesthetic I was working with. God’s Oasis (the commune we practiced in) was Shaw’s major creation. The house was filled with decor-rejects: found kitschy objects Shaw carefully sought out and arranged, and was also home to his extensive record and comic collections. God’s Oasis was our hangout, a major influence on us all.

The idea of creating fiction within the zine is interesting, because of our habitual self-mythologizing. Fragments of lyrics, films and stories were included in the zine, reflecting this hyper-creative atmosphere. I saw the collective as part of a socialist project—blending our art together, growing and overlapping in as many directions as possible. A lack of money and time cut the project short. Outside of the music, the zine enabled DAM to continue beyond its lifetime—and maybe that’s the fiction I wanted to tell, the myth of an immortal DAM.

In 2009, I assembled a show of DAM archives along with Printed Matter’s head of programming James Hoff. This Hungry for Death exhibit traveled around Europe and a few cities in the USA until early 2012—a project meant to level any hierarchy within DAM.

The last DAM archive show was curated by Kelley with Dan Nadel at PRISM gallery in Los Angeles. Kelley’s vision of the band was far different. It was a cleaner neatly framed and well-organized exhibit, showing the work as individual artists. A catalog for that show: Return of the Repressed tells the story. The show closed two weeks before Kelley’s suicide.

Laura: When the DAM zine appeared, the members were quite young and we can really feel that curiosity and freshness and at the same time we saw a big maturity trough the references and the way to conduct the project. DAM zine was really an art project, using a medium as a support for a group of artists, just as it was for the European avant-garde revue as Dada, Surrealistes, Situationnisme, Fluxus …. Was DAM in contact with this kind of project or similar project in the USA ?

Cary: We all admired the European avant-garde—and that was certainly a factor, but DAM’s radicalization happened around the political youth scene around Detroit and Ann Arbor. The White Panther Party (WPP), SDS, the Weathermen and Black Panthers were strongly active and left an indelible mark. We each were familiar with art history at a young age—before we met each other.

You can see certain affinities with art history in the first issue with Kelley’s manifesto, “What Destroy All Monsters Means to Me”, the kitschy, radical transgressive images and hyper-color presentation. We were caught in-between the movements of hippies and punks and proceeded to “fuck with” different parts of that, taking a post-apocalyptic stance. If left to develop further, it might’ve been transformative, perhaps something like the Cass Corridor movement in Detroit—or a branch of psychedelic pop-art.

We were also fans of artist Gary Grimshaw who made psychedelic posters for the Grande Ballroom and was Minister of Art in the WPP. His work was symbolic of revolution and altered consciousness, and that utopian outlook was also one we embraced.

We were inspired by the WPP, which was just breaking up when we came together. Kelley has said the WPP led him into the avant-garde arts and was the reason he became an artist. Shaw and I had a similar experience. The MC5, Stooges and the Detroit rock scene were inspiring to us. The Detroit Artist’s Workshop (DAW) was key to the radicalism of the Midwest. In April of this year a small exhibition was held at the Horse Hospital museum in London. This was the first time the DAW collective was recognized and displayed in Europe.

Since the late ‘90s, I’ve been collecting materials and writing on the DAW, the root collective behind the White Panthers. John Sinclair (manager of the MC5) and one of the founders of the DAW and Chairman of the WPP said, “Music is Revolution… and to look on each action as future history.” Being a culture worker was an important model for us. The name DAM was also a type of futile political/art slogan that could stand by itself. “All art is propaganda,” said George Orwell.

Laura: You are working on a book about Leni Sinclar [coming out soon through Foggy Notion] and I read that you started your shop Book Beat because of the DAW. Your bookshop and publishing activity seem to be a political and social project in the sense you want to be the voice of the underground and also take care of the future generation trough the children section you have in your store. Do you also see Book Beat as an art work too? A kind of in-progress big collage where books are the material like you use in your collage and films. Where does this special relationship to books, documents writing, and this attraction for the archivist activity come from ?

Cary: My teen bedroom was a scrapbook of scotch-taped underground news clippings; Jack Smith film stills, The Up band, posters of the MC5, and another of Sinclair looking like a mad bomber with daughter Sunny on his lap, munching a box of animal crackers. We discover ourselves as we grow out of childhood.

Many of these images were by Leni Sinclair and they informed my outlook. Guitar Army was filled with her work, and the art of Grimshaw, allowing me to see the power of photography and design. I saw how photography could be a weapon, a source for positive change. Art and politics came together at a young age. And the collecting bug also comes out of childhood—when posters, records and books first took on meaning.

One of my treasures as a junior hippie was the John Sinclair Freedom Rally poster of 1971, designed by Gary Grimshaw with a striking portrait of Sinclair shot by Leni. This was one of the first and perhaps only rock concerts with a political purpose: to free Sinclair from prison, receiving a ten-year sentence for possession of two marijuana cigarettes.

In 1998, I suggested that Leni Sinclair come to the Boijmans Van Beuningen museum in Rotterdam for the I Rip You, You Rip Me festival, an investigation into DAM and the Detroit avant-garde curated by Ben Schot and Ronald Cornellisen. This was the first survey of the Detroit avant-garde outside its hometown. To understand DAM as a regional group, it was best to start with Leni. She was the keeper of that time, her archive the photographic evidence.

In 1982, I opened a bookstore for many reasons, but perhaps most of all, it just seemed like a practical thing to do. I worked at other bookstores while making my way through college and thought this was something possible and could be a community resource. My wife Colleen developed the children’s department, which is now the strongest section of the store. Turning children onto reading helps insure future readers.

We think of the bookstore as a creative space, it’s also a personal laboratory—a place to think about art and new projects. For many years we showed artists and photographer’s work in a small backroom gallery and I learned a lot from those exhibits. Books are magical things, object that talk through the ages. They are portable time-machines. How amazing to read the thoughts of an author across time, having their voices come alive in your head.

Leni Sinclair » John Sinclaur and MC5, 1968

Laura: As an “ homme-bibliothéque “ (library-man) and a “published memory”, how do you explain this enthusiasm for the zine ? What look do you have on the current zine scene ?

Cary: The current scene is a confirmation of the beauty of the book as a physical object. A revival of letterpress has also exploded and is strong in Detroit, where there is a long history of industrial innovation and revolt against it. The return of the hand-made zine shows a positive opposition to weblogs, technological oppression, mass production and is another reaction to the lack of physical conversations taking place.

The zine revival of the ‘90s had good distribution, reviewers were common and there was an evolved network of support. Factsheet 5 was the best (and a huge) compendium of the scene. The need for reviews is essential for the scene to survive. The internet can serve as a review funnel but this still needs to grow in a more physical, substantial way. Public bookstores and specialty shops are needed to make the work more accessible. Zine festivals such as Rebel-Rebel are a great service, and need to expand. Zines represent potential and experiment. They are often a starting point for many artists: portable galleries of ideas and images, a place where risk can still find reward.

Artist zines in the ‘70s had a shallow following and the network was weak. Except for underground comics, most zines were traded as mail art. Printed Matter of New York was one of the few guiding lights then and is thankfully still around. Recent interest in historic work has grown to a respectable level. Museums are collecting them — even displaying the work. When something so ephemeral and obscure returns to life, it sends out a ray of hope.

The Jazz age may be gone but its spirit is alive. Revolutions always begin underground where they can stay hidden for years, gathering strength below. The zine revolution is once again percolating, searching for air. It comes at a time when resistance is most needed.

An altered version of this conversation was previously published in The new spirit of vandalisme special N°10 special « Festival Rebel Rebel : fanzine art & culture » – Avril 2016

Photo Credit on the banner : « Cary Loren photo by Cameron Jamie, 2011 »